Category: Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS)

Nuclear Weapons Solutions

Progress on US nuclear weapons policy may be slow and incremental—but it’s possible.

Roughly 9,000 nuclear weapons are hidden away in bunkers and missile siloes, stored in warehouses, at airfields and naval bases, and carried by dozens of submarines across the world.

A single warhead can demolish a city center. A full-fledged nuclear war would threaten life as we know it.

But the risk of nuclear war isn’t fixed; with the right policies and safeguards, we can help protect against mistakes, accidents, and poor decision-making—and we can work toward a world free from the nuclear threat.

No-first-use

Nuclear weapons are meant to deter nuclear attacks from other countries. However, current policy allows the United States to begin a nuclear war by being the first to use nuclear weapons in a conflict—in response to a non-nuclear attack by North Korea, Russia, or China. A “no-first-use” policy would take this option off the table. The United States could pledge that it will never be the first to use a nuclear weapon, regardless of the circumstances. Doing so would reduce the risk of miscalculation during a crisis, and limit the possibility of a smaller, non-nuclear conflict escalating into a nuclear one. Without no-first-use, the US public is at risk of a devastating retaliatory attack, should the United States ever cross the threshold and start a nuclear war.

Sole authority

In the United States, the president is singlehandedly responsible for the decision to launch a nuclear weapon. They are not required to consult with anyone, and no one carries the authority to stop a legal launch order once given.

This system of control (known as “sole authority”) isn’t the only way to handle launch decisions. Other officials could securely be included in the decision, providing checks and balances and a basic defense against mistakes, accidents, miscalculations, and recklessness.

De-alerting

Currently, 400 nuclear-tipped missiles in the US heartland are kept on “hair-trigger alert.” If sensors show an incoming nuclear attack that threatens these missiles, it’s US policy to alert the president, who would need to order their almost immediate launch to prevent them from being destroyed—before the attack is confirmed as real.

But sensors can be wrong. A long list of nuclear close calls—which include technical malfunctions, miscommunications, and plain bad luck—shows how close we’ve come to mistakenly starting nuclear war.

Taking these missiles off hair-trigger alert (or “de-alerting”) would immediately remove the risk of a mistaken or accidental launch, while preserving our ability to retaliate with missiles on submarines hidden at sea.

Smarter spending

The United States is currently planning to spend an estimated $1.7 trillion dollars over the next three decades to maintain and replace its entire nuclear arsenal with new weapons, including nuclear-armed bombers, missiles, and submarines.

Such a tremendous investment of money and effort is unnecessary. It also encourages Russia to build more capable weapons of its own, accelerating an emerging and destabilizing international arms race.

Instead, the United States should eliminate some types of nuclear weapons, refurbish the remaining weapons where possible, and make any necessary replacements without enhancing capabilities.

International agreements

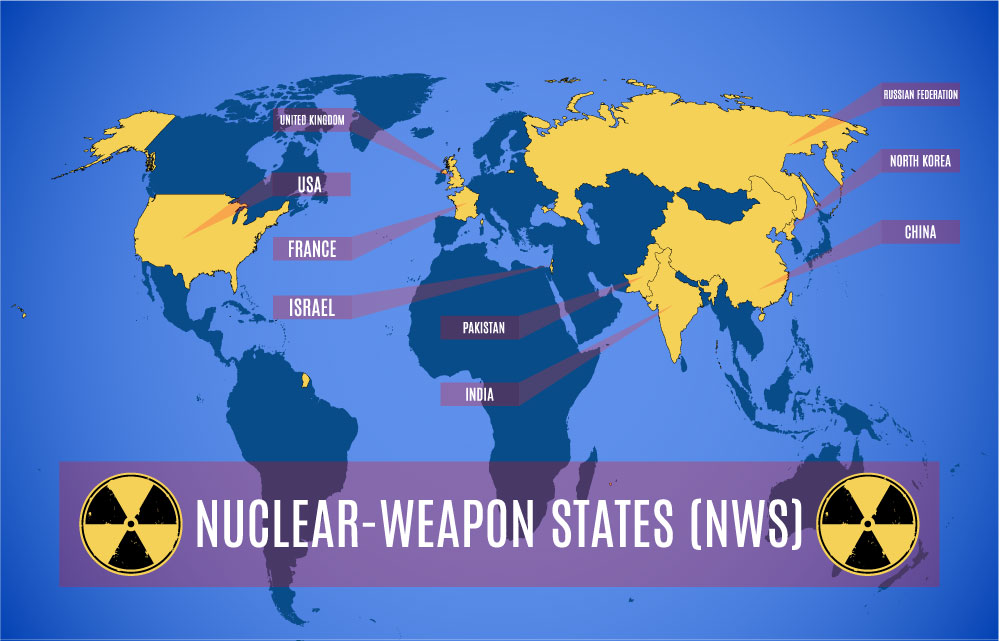

A total of nine countries possess nuclear weapons. Reducing the risk of nuclear war will require domestic policy changes within all those countries, as well as cooperation and verified agreements between them.

Diplomacy has a strong track record. Multiple treaties and agreements—and decades of dialogue and cooperation—helped reduce US and Soviet arsenals from a high of 64,000 warheads in the 1980s to a total of around 8,000 today.

The United States should build on those successes by extending the New START Treaty with Russia; committing to a “diplomacy first” approach with North Korea; and rejoining the Iran Deal, which limits Iran’s capacity to produce weapons-grade uranium.

Nuclear Weapons Worldwide

Thousands of nuclear weapons exist in the world. The use of even one could change life as we know it.

Nine countries possess nuclear weapons: the United States, Russia, France, China, the United Kingdom, Pakistan, India, Israel, and North Korea.

Some countries first developed nuclear weapons in the context of the Cold War, as the United States and the Soviet Union jockeyed for influence. Others developed them more recently, in response to regional conflicts or other concerns.

US-Soviet and US-Russian treaties and agreements have reduced the total global stockpile of weapons, which peaked in the 1980s at some 60,000 weapons—but 9,000 still remain. The nuclear policies of these nine nations increase the risk that these weapons will be used.

US nuclear weapons policies are alarmingly dangerous.

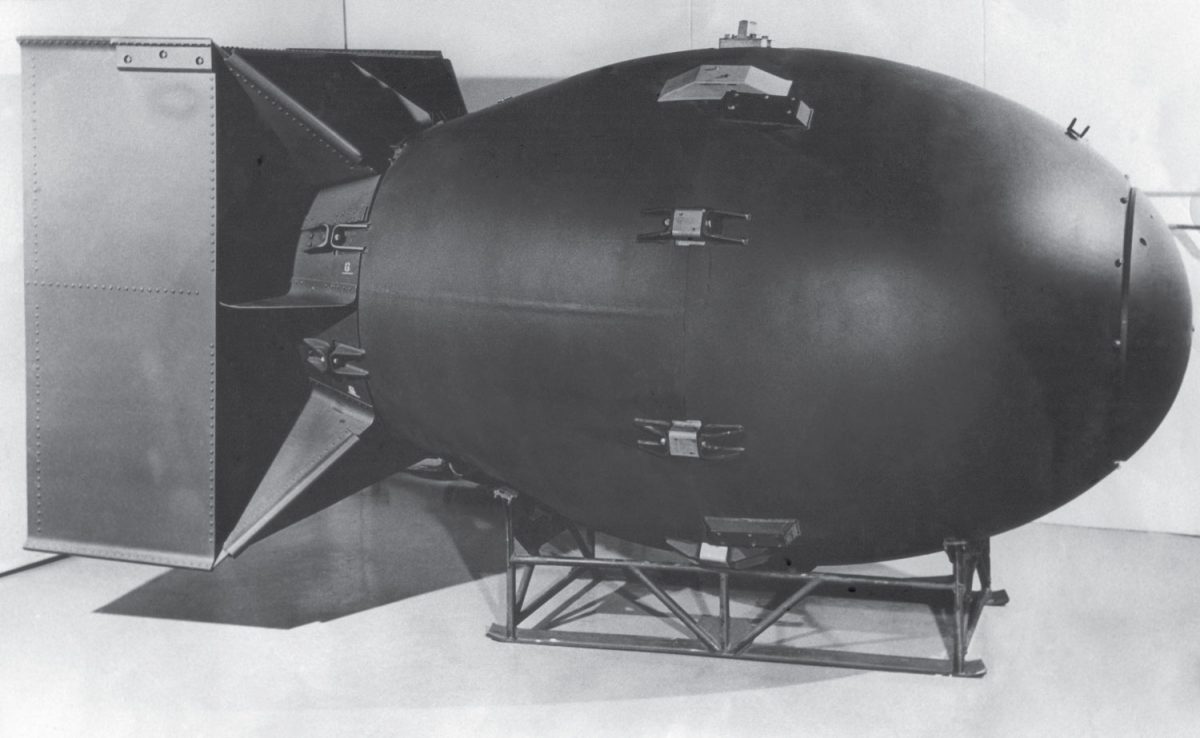

The United States tested the first atomic device in July of 1945. Seven years later, it exploded the first thermonuclear weapon—designed in part by Richard Garwin, who now serves on the board of the Union of Concerned Scientists.

In the following years, the United States amassed many thousands of nuclear weapons, each capable of immense destruction. At the height of the Cold War, the United States maintained roughly 30,000 nuclear bombs and warheads, though the total number of weapons has fallen, thanks in part to US-Soviet and US-Russian treaties and agreements.

The policies governing when, where, and why the United States would use nuclear weapons remain unconscionably risky.

The US arsenal

As of 2019, the US arsenal contained some 3,800 nuclear weapons, 1,750 of which are deployed and ready to be delivered. Their destructive capabilities range widely: the most powerful weapon—the “B83”—is more than 80 times more powerful than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. The smallest weapon has an explosive yield of only 2 percent that of the Hiroshima bomb. Such “low-yield” weapons are designed to be used on the battlefield, increasing the likelihood they may actually be used.

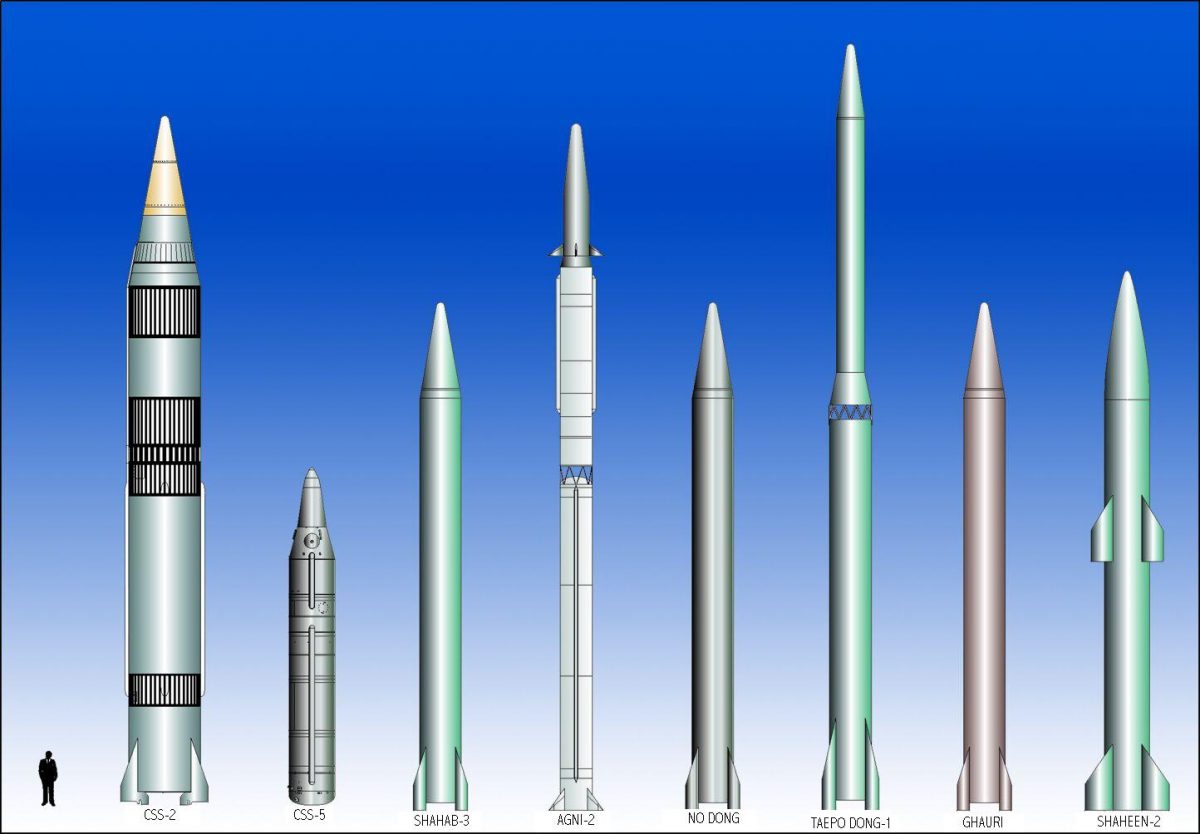

The country’s weapons are deployed in submarines and in 80-foot-deep missile silos across the western United States. Others are stored at air force bases, where they can be loaded on long-range bombers. Some 150 US bombs are deployed at airbases in five European countries.

The arsenal’s primary purpose is “deterrence”—i.e., it’s intended to dissuade others from launching a nuclear attack. However, current policies allow the United States to use nuclear weapons first against Russia, China, or North Korea, effectively beginning a nuclear war.

New weapons

Over the coming years the Pentagon plans to spend more than a trillion dollars maintaining and rebuilding the entire US nuclear arsenal, which is both unnecessary and unwise. US weapons are maintained and upgraded on an ongoing basis and many don’t require replacement. Certain types should be eliminated altogether because they are redundant and provocative.

The main outcome of the Pentagon’s spending spree may be to spark an arms race with Russia and China, which would be expensive and dangerous—especially in the absence of strong arms control agreements.

Policies

The risk of nuclear war has as much to do with policy as it does to do with the weapons themselves.

In the United States, the President is granted sole authority to launch nuclear weapons. He or she doesn’t need to consult with anyone beforehand and can issue a launch order with very few checks and balances.

It’s also US policy that nuclear weapons can be used first in a non-nuclear conflict with a nuclear-armed state, i.e. not only in retaliation. If the United States crossed the nuclear threshold and started a nuclear war, it would open up our country to a retaliatory attack.

Additionally, 400 land-based missiles are kept on hair-trigger alert, meaning they’re maintained in a ready-for-launch status. Current policy allows the United States to launch these missiles on warning of an incoming attack, despite a long history of false alarms and close calls.

Collectively, these and other policies increase the risk of nuclear war. Better policies would reduce that risk.

They’re the most dangerous invention the world has ever seen. Can we prevent them from being used again?

What we’re facing

When the United States dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima, the destruction was unlike anything experienced before. Tens of thousands of people died instantly. An entire city was destroyed in the flash of a single bomb.

Today, some 9,000 nuclear weapons remain in the world’s arsenals—with over 90 percent owned by the United States and Russia. Both countries are actively planning to build new weapons, sparking a 21st century arms race and increasing the risk of nuclear war.

Meanwhile, many of the Cold War’s most absurd and dangerous nuclear policies remain unchanged. In the United States, the president can order the launch of nuclear weapons without consulting anyone. And US policy allows it to use nuclear weapons first in a non-nuclear conflict with Russia, China, or North Korea—likely starting a nuclear war.

These policies and plans threaten the world in very real ways, and they need to change. You can help.

All Things Nuclear

All Things Nuclear

Read More

Reducing the Risk of Nuclear War

Taking Nuclear Weapons Off High-Alert

Accidental nuclear war is more often portrayed as the subject of science fiction, not an actual possibility.

But despite the Cold War ending decades ago, the United States and Russia still keep hundreds of nuclear weapons on high alert, ready to launch. Also known as “hair-trigger alert,” this rapid launch option significantly raises the risk of an accidental, unauthorized, or mistaken nuclear attack, with no appreciable benefits to national security.

On its surface, the system is simple: if we detect and verify a nuclear attack, we’ll launch our own missiles before they’re destroyed. But the process must occur within minutes, and relies heavily on error-prone radar, satellite, and human communication systems, all of which are susceptible to false alarms and, potentially, cyberattack. And because the timeframe is so short, the military depends on scripted nuclear launch procedures that are routinely rehearsed, biasing the process toward a decision to launch—especially in times of crisis.

From faulty computer chips to simple human mistakes, dozens of near misses and safety accidents illustrate these and other shortcomings. No single incident has caused an accidental, unauthorized, or mistaken launch yet—but the probability is not zero. The more incidents that occur, the greater the chance that, due to confusion and an unforeseen confluence of events, one of them will lead to disaster.

Arguments for retaining high alert

Because land-based nuclear missiles are stored at known locations, they are vulnerable to attack. Hair-trigger alert was originally intended to ensure that, were the missiles targeted, they could be launched in retaliation before being destroyed. Yet the United States’ retaliatory capabilities are already ensured by hundreds of nuclear weapons stored on submarines, which can’t be targeted. As a deterrent, the high alert status of U.S. land-based missiles is therefore irrelevant.

Some experts argue that de-alerting could lead to a “re-alerting race” during a future crisis, in which two quarreling sides raise their alert levels in a high-stakes game of “tit for tat,” exacerbating tensions. But this is premised on the notion that rapid-launch missiles are needed for deterrence, which is untrue.

Others argue that hair-trigger alert is needed for “extended deterrence,” ie, the assurance to others—particularly Japan—that the United States will provide nuclear retaliation on their behalf. But extended deterrence depends on the U.S.’ willingness to retaliate, not the speed of its decision. Numerous Japanese leaders have, in fact, expressed enthusiasm for U.S. de-alerting.

How to de-alert nuclear missiles

The U.S. should eliminate options for quickly launching missiles on warning of attack, and take its missiles off hair-trigger alert. At present, land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) in the United States are stored in underground siloes and controlled by nearby launch centers. Removing them from hair-trigger alert could be as simple as manually activating a safety switch that prevents the missile from being launched (these switches already exist and are used by maintenance crews). When the next false alarm occurs, leaders would then not be under the same pressure to launch, eliminating the risk of a mistaken launch, and reducing the risk of an accidental or unauthorized launch.

The time for change is now. Despite promises as a candidate and early in his first-term, President Obama’s administration decided not to end hair-trigger alert during its 2010 Nuclear Posture Review. The security environment has, however, changed. Tensions between Russia and the United States are higher than they have been in decades, and China is considering placing its nuclear arsenal on high alert for the first time, citing U.S. security capabilities. In a cautionary 2015 address, former U.S. Secretary of Defense William Perry declared: “today we now face the kind of dangers of a nuclear event like we had during the Cold War, an accidental war.”

Taking nuclear weapons of hair-trigger alert would be a strong first step toward ensuring nuclear war remains the stuff of fiction.

In this report

Close Calls with Nuclear Weapons

Close calls have nearly led to the launch of nuclear weapons—and the risk is still there. Learn about past incidents and current issues here. Report

Leaders Urge Taking Weapons Off Hair-Trigger Alert

A surprising number of high-level politicians and generals have called for an end to hair-trigger alert.

Downloads

The US Nuclear Arsenal

Here’s every nuclear weapon in the US arsenal.

Each point represents a nuclear weapon—the most destructive device on Earth. The US nuclear arsenal includes over 4,600 weapons.